PARIS, France — Chanel, by far the world’s top-selling luxury megabrand, is not for sale, according to its owners. Time and again, the billionaire Wertheimer family, which has held a stake in Chanel since the 1920s, has denied through its representatives any intentions of relinquishing control over the crown jewel in its empire. And yet, rumours persist among potential investors, bankers and the wider European luxury industry that Chanel could be bought — for a price.

The valuation, insiders say, would reach $40 billion, if not $50 billion. There is even talk of a financial dossier circulating amongst investors, although Chanel denies this as well. In an interview on Friday just before the brand’s Cruise 2020 show, Bruno Pavlovsky, president of fashion and Chanel SAS, dismissed the possibility.

Rumours and fake news are part of this new world.

“Rumours and fake news are part of this new world. That will continue to happen,” he said. “We’re not going to be able to change that. At the end of the day, what’s most important is what you see and what the brand is communicating. That gives you a real picture of what the brand is today.”

For investors, the rumours may simply be a case of wishful thinking. After all, capturing control of Chanel — which generated revenue of nearly $10 billion in 2017, marginally less than Louis Vuitton, but much more than LVMH’s cash cow in retail equivalent terms — would be the ultimate achievement for modern luxury’s deal-makers.

But there are also practical reasons for believing the Wertheimers might be ready to sell Chanel. In 2018, the company released financial information to the public for the first time in its history in the face of claims that its brand image was getting dusty and that this was impacting business performance.

The concerns surfaced when a report filed in 2017 to the Dutch Chamber of Commerce by an entity called Chanel International BV — a private limited-liability company that was incorporated in the Netherlands and reflects a significant portion of the overall business — indicated that sales momentum was slowing in parts of the world. In 2016, annual sales of Chanel International B.V. were under $6 billion, down about 10 percent from the previous year, while net income fell almost 35 percent from $1.34 billion to $874 million. Operating income dipped 20 percent to $1.28 billion.

Last summer, when Chanel released its full financials for the first time via Chanel Limited, a corporate entity established in the UK that encompasses the global business, the stated rationale was proving the company’s financial health and rebuffing persistent rumours that Chanel could be a takeover target.

Chanel plans to report again this year, presenting annual sales for 2018 in June. “We want, first, to stop the fake news about the brand and we want to be able to give to our customers, our partners — suppliers — transparency about the situation, the impact and the power of the brand today,” Pavlovsky said. “The best way to do so is to just give the financial results.”

Such declarations, however, can also help to burnish a brand’s image and make it even more attractive to potential buyers. According to a source with knowledge of Chanel’s internal operations, there is interest from multiple Asian buyers and a buyer in Mexico, described as “deep-pocketed and discreet.”

The fact that Chanel issued a $3.4 billion dividend to its owners in 2016 — double the year before — also suggests that the firm could be getting ready to return value to the family, given that it would be easier to divide liquid assets, one banking source said.

That said, it seems the Wertheimer family intends to maintain a significant interest in the business going forward and is currently training Chanel’s next generation of executives to take on larger roles, including the children of current chief executive Alain Wertheimer, 70, grandson of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel’s business partner. His brother, Gérard Wertheimer, who is in his late 60s, maintains a behind-the-scenes role, while their half-brother, Charles Heilbronn, runs Mousse Partners Limited, the family investment firm. (Heilbronn’s son, Arthur, is also involved.)

“They will come step by step into the business,” Pavlovksy said of the next generation. “It’s their choice, their rhythms. I can guarantee you that they’re organising the next steps, but there’s no hurry. They’re here and they’re doing their job.”

Some observers believe that between the current generation of leaders and their offspring, an outside chief executive may take the reins while the Wertheimer and Heilbronn children gain more experience. For nearly a decade, American retail executive Maureen Chiquet held the role of global CEO, although she was fired from the company in January 2016 after “differences of opinion about the strategic direction of the company,” according to a statement the brand released at the time. The company has since said that Alain Wertheimer, who originally said he would only occupy the chief executive role temporarily, is staying put for the foreseeable future.

“Who might come next is not on the agenda,” chief financial officer Philippe Blondiaux told the New York Times last year. To be sure, the chance of any major changes occurring on the executive side, where one family has successfully controlled the business through several decades and three generations, now heading into four, are minimal, at least for the time being.

Swifter change on the creative side is far more possible. Chanel remains the world’s most desirable luxury brand and has appeal across generations, but digital disruption and the rapid maturation of Chinese consumers have reshaped the luxury sector. Shoppers are craving newness like never before.

In a fast-moving market, Chanel’s collections, stores and marketing could use a refresh. And while many of its efforts — including its spectacular runway shows, which light up social media — continue to resonate, the company will need to evolve in order to maintain its advantages.

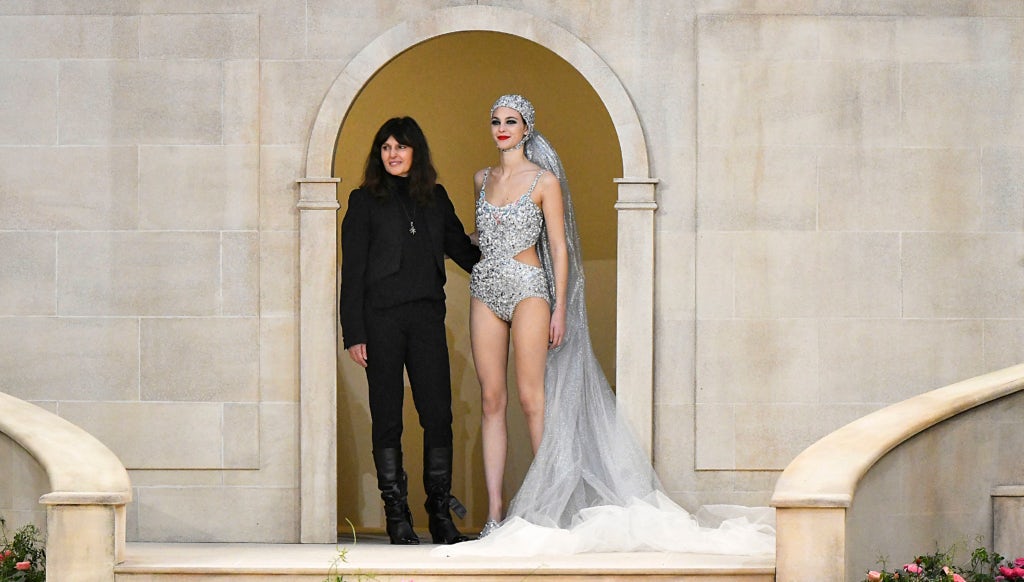

Longtime designer Karl Lagerfeld, who passed away in February 2019, was not only the mastermind behind ready-to-wear and couture, but the entire brand image. In a bid for continuity, his role has been split into two. Longtime studio director Virginie Viard now oversees fashion collections, and longtime image director Eric Pfrunder oversees marketing, advertising and other consumer messaging.

Virginie Viard and Vittoria Ceretti during Chanel’s haute couture Spring/Summer 2019 show in Paris | Source: Getty Images

“Virginie knows everything about Chanel, about Mademoiselle Chanel,” Pavlovsky said, characterising her appointment as a strong choice. “She has been working for the past 30 years with Karl. She has been part of the development of the métiers d’art. In fact, she knows everything.”

Yet Viard’s and Pfrunder’s staying power without Lagerfeld at the helm is far from clear. Many industry insiders believe that while the approach makes sense for a period, Viard, who has never sought the spotlight, and Pfrunder, a disciple of Lagerfeld’s, are not a long-term solution. Rumours persist that former Celine designer Phoebe Philo, who many see as the Coco Chanel of her generation, will eventually assume the role, although Chanel continues to dismiss this notion and Philo may not be interested in returning to a big brand anytime soon.

“I hear the rumours [about Philo] and all that, and I find that quite funny,” Bruno Pavlovsky, president of fashion and Chanel SAS, told BoF in December 2018. “But it’s nothing serious.”

As for the direction of the wider company, Luca Solca, managing director of luxury goods at Sanford C. Bernstein Schweiz, said that while an IPO, merger, investment or strategic acquisition are all possible outcomes, the most likely scenario would be that Chanel maintains the status quo. “The likelihood of alternative options is probably 30 percent,” he said.

If the Wertheimers were inclined to sell, major motivations would be to secure the fortunes of future generations, or to exit a business that the fourth generation was not interested in running. Fashion is not what it was even 10 years ago, let alone 40, when Karl Lagerfeld developed the much-imitated business model that helped to turn family-run luxury houses like Chanel into multi-billion-dollar global powerhouses. Today, Chanel’s rivals, from LVMH to Kering to Hermès, are better equipped than ever to compete.

And yet, Chanel is still on top when it comes to retail sales and creating tremendous value for the Wertheimers.

“The current generation of Chanel shareholders seem more inclined to keep it as a family business,” said Mario Ortelli, managing partner at Ortelli & Co. “But we can be proven wrong.”

Chanel certainly has plenty of options:

Scenario #1: Sell to a Strategic

There aren’t many strategic groups that could afford Chanel. LVMH chairman and chief executive Bernard Arnault, long thought to admire Chanel has dismissed speculation that the group is eyeing an acquisition as “fake news,” despite rumours that he had met with the Wertheimer family.

“Chanel is a magnificent business, but we have had no contact with them,” he said in 2018 at LVMH’s annual shareholder meeting.

Such a deal, however, would be a “way to build a true industry giant,” Solca said, given the synergies between the two firms, from manufacturing — both own several specialist firms in Italy and France — to beauty.

With free cash flow of nearly €3 billion, luxury group Kering is also positioned to acquire a big, profit-boosting brand. While chief executive François-Henri Pinault has said the company doesn’t need acquisitions to grow, and therefore wouldn’t engage in a price war, he’s not ruling it out.

“Of course, if opportunities present themselves that are consistent with our portfolio rules, in terms of market positioning and style, we will be able to seize them,” Pinault said in February 2019. “We have the financial means, and we also have platforms capable of embracing new labels and tapping their potential relatively quickly.”

However, Kering’s current market capitalisation is a little over €60 billion, not much more than Chanel’s estimated private valuation, which means the megabrand would be a lot for the group to absorb.

While rumours have circulated that Mayhoola, the luxury investment fund backed by the Qatari royal family, is interested in Chanel, such a partnership currently seems unlikely given that Mayhoola continues to divest from its fashion interests, disposing of its stake in Anya Hindmarch and entertaining a sale of Valentino earlier this year.

A left-field but possible acquirer could be a beauty conglomerate such as L’Oréal, given the scale of Chanel’s beauty business. The brand does not break out its sales by category, although analysts estimate that it generates more than $3 billion a year selling beauty products.

“Chanel has a remarkable business in beauty,” Ortelli said. “Because of that, big beauty might be interested in acquiring and managing the entire company.” The drawback, of course, is that most beauty players do not have the fashion expertise required to run Chanel.

Scenario #2: Merge With a Strategic

While few luxury groups can afford to take over Chanel outright, a merger would result in a strategic alliance that further strengthens both sides of the business and capitalises on shared services, including manufacturing, distribution and advertising. It would also likely allow the Wertheimer family to maintain an active role in decision making. Potential partners here include Kering, but also Swiss group Richemont, which is complementary to Chanel.

“Chanel is strong in leather goods and beauty, Richemont in watches and jewelry,” Solca said. Such a partnership would afford “all the rewards of a bigger-sized company,” Solca added, although Richemont’s status on the public market could be a blockade.

There is also the matter of two family-run businesses suddenly making decisions as one unit. (Richemont’s biggest shareholder is its founder, Johann Rupert.) For this reason, it’s unlikely that Hermès and Chanel would merge. While there is a shared respect between the families, neither is likely to relinquish control to the other.

Scenario #3: Sell to an Investor

It is perhaps the most unlikely scenario of all, but there are certainly plenty of private investors, including private equity funds and family offices, that would be interested in owning Chanel. For the brand, the benefits of such an arrangement are murky, however. Private equity is usually a tool for medium-sized brands to scale up quickly. Chanel already has scale and plenty of cash.

Regardless, according to a source with knowledge of the inner workings of the company, there are multiple Asian parties, as well as an investor in Mexico focused on European acquisitions, that are interested. A sovereign wealth fund, such as Singapore’s Temasek, is another option. However, most of these acquisitions would be made with the understanding that the company would eventually sell shares to the public, which could create more distance between the Wertheimer family and Chanel than desired.

Scenario #4: Partial Flotation or IPO

In 2018, Chanel’s decision to release the details of its financial performance for the first time ever caught the attention of the markets. While an initial public offering seems unlikely, the company could choose to conduct a partial flotation à la Hermès, which would give the family an opportunity to cash out while remaining in control of the business.

However, this comes with a risk of a hostile bid, depending on the quantity of free flotation. (Hermès spent four years fighting off the advances of LVMH in a public battle for shares. LVMH finally backed down, relinquishing its shares in 2014.)

If Chanel chose to float 25 percent of the business, there is little risk of takeover, except if the family entered a dispute. If a family member formed an alliance with an outside entity, it could shift the balance of power, allowing another group or investor to control the business.

But if Chanel was interested in acquiring more brands and creating its own group, an IPO could be advantageous. (It already owns swimwear lines Eres and Orlebar Brown.) Company stock can be used as currency, which makes acquisitions easier. Such a scenario would likely require Chanel to cultivate another high-profile designer in the vein of Lagerfeld to replace Viard, as the market pays close attention to mass consumer perception.

Industry observers are skeptical.

Chanel doesn’t need cash, so why would they do an IPO?

“The market has been fantasising about an IPO,” said one industry analyst. “Chanel doesn’t need cash, so why would they do an IPO? When Hermès chief executive Jean-Louis Dumas sold a small percentage of its shares to the public, it was in order to finance expansion. Chanel doesn’t need to fundraise.”

Scenario #5: Maintain Status Quo

What happens if the Wertheimer choose to do nothing?

Gerard Wertheimer (L) and Alain Wertheimer (R) in 2011 | Photo: Julien Hekimian for Getty Images

There is already a succession plan underway. Chanel owners Alain and Gérard Wertheimer have a total of five children between them. Mousse Partners’ executive Charles Heilbronn, half-brother to Alain and Gérard, has three. According to two sources familiar with the business, the fourth-generation heirs have taken more active roles in the past few years as they enter their thirties.

Nathaniel Wertheimer, son of Alain, and Arthur Heilbronn, son of Charles — both Harvard graduates — are contenders to take over the business. At one time, Nathaniel worked at Estée Lauder Companies to learn about cosmetics, an important category for Chanel. One source with inside knowledge of the company said that Nathaniel could take Alain’s role, either the position of global chief executive or chairman, and Arthur could carry on his father’s activities at Mousse Partners, including acquisitions and real estate. Both have spent time at Chanel’s subsidiaries to learn more about the operations.

Sometimes, a family-run company will hire an outside CEO until the next generation is prepared to run the business.

“Chanel could also promote in-house talents on the executive side; there’s no shortage of talent in the company,” Solca said. Pavlovsky, the longtime head of fashion, was recently made president of Chanel SAS, indicating an expansion of his role.

Looks from the Chanel Cruise 2020 Collection at Le Grand Palais | Source: Courtesy

But regardless of who exactly takes the reins, a “status quo” scenario could involve a creation of a financial trust, if the family has not already established one, in order to provide management and protect assets, as per the specific instructions laid out by the third generation.

Trusts are a conservative way to run a business: trustees are not owners or shareholders but rather custodians that are bound to established rules, one of which would likely prevent the four-generation heirs from selling.

The company could also establish a non-profit, charitable foundation, which could be structured as a trust.

“This works fantastically for Rolex,” Solca said. In 2016, Giorgio Armani set up a foundation in his name to “safeguard the governing of its assets,” which essentially means that it will be hard for another group to buy his business, of which he is currently the sole shareholder.

The choice to move Chanel’s global headquarters, including its finance, human resource and legal departments, to London in 2018 could be helpful when optimising its tax plan for the generational change. At the time, the company said that it “wanted to simplify the structure of the business and London is the appropriate place to do that for an international company. London is the most central location to our markets, uses the English language and has strong corporate governance standards with its regulatory and legal requirements.”

Discover more from ReviewFitHealth.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.