What Thomas Jefferson Ate – White Bean Soup

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, has a firmly rooted role in American food history. A naturally curious and creative individual, Jefferson embraced the relationship between garden and table. His Virginia plantation Monticello was a place of horticultural creativity and ingenuity; his gardens were home to a number of unique (what would now be considered heirloom) vegetables and fruits. As Minister to France, Jefferson learned a great deal about French cuisine and cooking methods, often recording recipes in his own hand. While in Washington, he became know for throwing the finest dinners the President’s House had ever seen. Jefferson’s Monticello kitchen blended Southern Virginian cooking styles with Continental cuisine, while also incorporating the African cooking influences of his enslaved staff. He had an important impact on the national culinary consciousness, combining food traditions from the Old World and the New World to create a uniquely American approach to cooking.

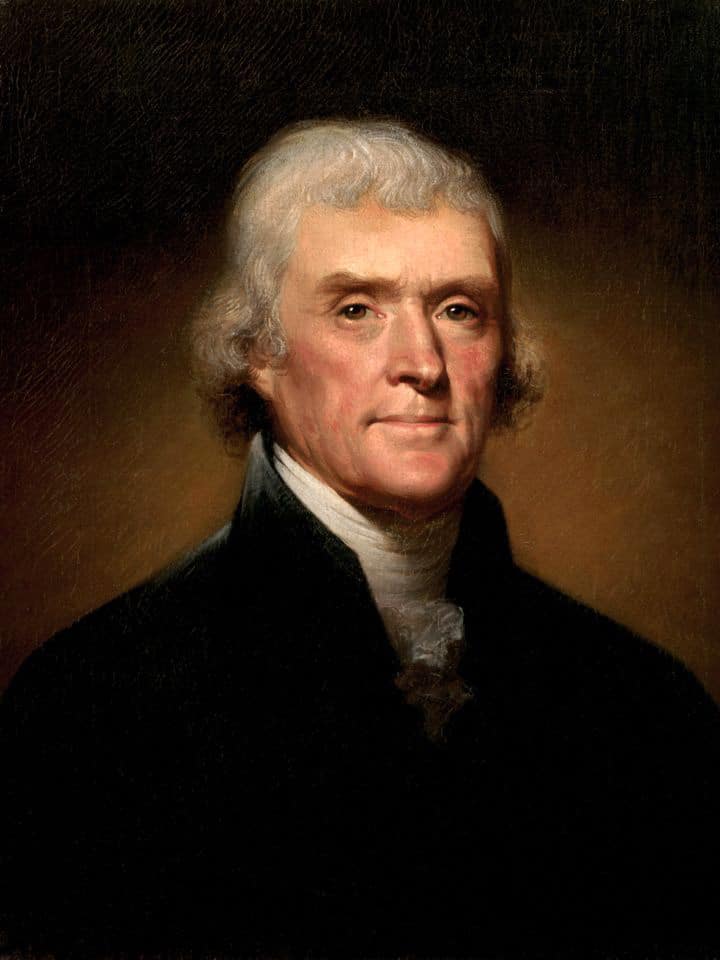

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800. Courtesy of the White House Historical Association

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800. Courtesy of the White House Historical Association

While living at Monticello, Jefferson kept a detailed notebook about his kitchen garden, recording the planting of hundreds of varieties of fruits, vegetables, and herbs. He was always in search of new additions to his garden collection. He planted all kinds of things, from Italian grapes to French tarragon to Texas peppers to Irish wheat. He was known to admire Continental gardening styles, and used the book “Observations on Modern Gardening” by British author Thomas Whaley as a resource when planning his own gardens at Monticello. Jefferson was drawn to Whaley’s description of the ferme ornée (ornamental farm) concept, a style of garden that combined the agricultural working farm with the beauty of a pleasure garden. The style is reflected in the ornamental yet functional design of the gardens surrounding Monticello. The records he kept of the various vegetables and fruits he planted have proven extremely helpful to food historians, providing insight into the burgeoning culinary identity of the newly formed American colonies.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-Gardens-Jefferson.jpg

The gardens at Monticello

The gardens at Monticello

Jefferson was intellectually curious about many subjects, and food was clearly a particular passion. He recorded at least 10 recipes by hand, including a classical French cooking practice which he titled, simply, “Observations on Soup”:

Always observe to lay your meat in the bottom of the pan with a lump of fresh butter. Cut the herbs and roots small and lay them over the meat. Cover it close and put it over a slow fire. This will draw forth the flavors of the herbs and in a much greater degree than to put on the water at first. When the gravy produced from the meat is beginning to dry put in the water, and when the soup is done take it off. Let it cool and skim off the fat clear. Heat it again and dish it up. When you make white soups never put in the cream until you take it off the fire.

Jefferson was appointed Minister (plenipotentiary) to France from 1785 to 1789. While in Europe, he spent a good deal of time exploring French cuisine and cooking methods. He became an expert on French wines, and he even brought a slave from Monticello named James Hemings with him to learn French cookery. When Jefferson took the Oath of Office in 1801, one of his first priorities was finding a suitable French chef for the President’s House kitchen. During Jefferson’s time, and for several decades after, French food, serving styles and social graces were considered the ultimate in refinement. We can still see this fondness for French food styles in America today.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Jeffersons-House-in-Paris.jpg

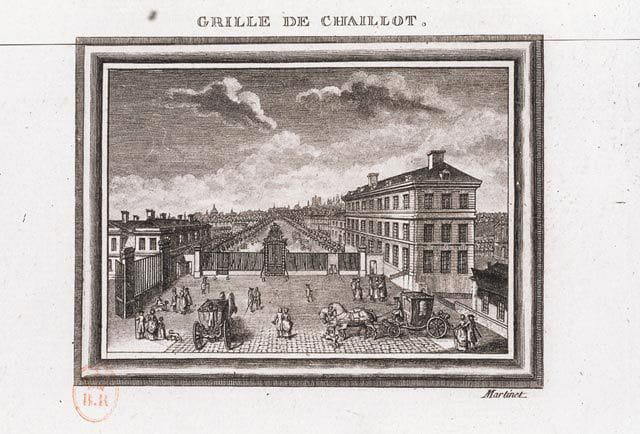

Jefferson’s House in Paris, courtesy of the University of Virginia.

Jefferson’s House in Paris, courtesy of the University of Virginia.

The French-inspired recipe for White Bean Soup in today’s blog appears in a Monticello cooking manuscript compiled by Jefferson’s granddaughters, Virginia Randolph Trist and Septimia Anne Randolph Meikleham. In their notes, they write that the recipe was brought over by their uncle, Gouverneur Morris, from one of his trips to Europe. It is a simple and classic white bean soup, pureed and served over warm grilled bread croutons. The dish is vegetarian; it makes a delicious and healthy winter meal. At Monticello, it would have been served as one of several appetizers in a multi-course meal. Thomas Jefferson was known to have a fondness for vegetables and kept meat consumption to a minimum—in his words, “I have lived temperately, eating little animal food, and that is not an aliment, so much as a condiment for the vegetables which constitute my principal diet.” This soup is a great example of a meat-free dish that surely made an appearance on Thomas Jefferson’s dinner table.

I first read this recipe in the book “Dining at Monticello,” a beautiful hardback volume (now out of print) that combines scholarly essays, illustrations, and recipes to give a broad overview of what food was like at Jefferson’s colonial-era Monticello. I have not yet been able to obtain the original recipe verbatim (I have a request pending at the Jefferson archives), so I’m relying on editor Damon Lee Fowler’s transcription. He notes that he had help from noted food historian Karen Hess, so no doubt this is a very accurate transcription. I’ve added pepper to the soup according to taste; pepper was widely available at the time, and I don’t think it would be out of place in this type of soup. While the soup was nice with salt alone, the pepper definitely improved the flavor. Otherwise, the recipe remains untouched from Mr. Fowler’s transcription.

Update: I received a scan of the original recipe from the Jefferson archives. Here is the recipe from the Meikelham and Trist Manuscripts, verbatim, for those who are interested. It is indeed quite similar to Fowler’s transcription. Words with question marks were illegible on the scan.

Bean Soup

Put 1 qt. beans in soak at night; the next morning put them into a pot with some salt and 1 gal. cold water; afterwards put in some carrots & turnips * 1 parsnip, the first scraped, the second (& third) peeled, and both cut up in small pieces. Set the pot to one side of the range, skimming it as you do other soups, and let it simmer for 5 or 6 hours. After the vegetables have (become?) soft, pass the whole through the colander & put it back in its pot. About half an hour before the soup is taken off, cut up some stalks of celery and put them in. Fry or toast some thin slices of bread & cut them up in small pieces & put into the tureen in which the soup is to be served; then pour it on the bread. If the bread is fried, cut it up before putting it in the pan. If the soup gets too thick in boiling, add boiling water to it; it may be, you may add in the (?) – the time that it is on the fire, two quarts more or less. The quantity here directed will make soup for two days for a family of an ordinary size.

– Governor Morris the Elder

* The beans ought to be washed and picked before putting them in soak, or using them without soaking, in which (best?) case they take longer to boil.

* These roots need not be put on directly with the beans, the carrots should be put on first of them, then turnips, then parsnip last.

Recommended Products:

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Monticello White Bean Soup

servings

8 hours

2 hours

Parve or Dairy, depending on preparation

Description

Learn a colonial recipe from Thomas Jefferson’s family at Monticello for White Bean Soup. Vegetarian, healthy, delicious historical recipe.

Ingredients

- 1 1/2 lbs dried navy, great Northern, or cannellini beans (4 cups)

- 16 cups water (4 quarts)

- Salt and pepper

- 2 large carrots, trimmed, peeled, and diced

- 2 small turnips, trimmed, peeled, and diced

- 1 medium parsnip, trimmed, peeled, and diced

- 3 large ribs of celery with leafy green tops, chopped

- 2-3 tbsp unsalted butter

- 4 slices rustic artisan bread, sliced 1/2 inch thick

Recipe Notes

You will also need: a large soup pot or 6-quart Dutch oven

Instructions

Rinse and sort the beans, removing any stones or impurities. Drain the beans and put them in a large bowl, then cover by a few inches of cold water. Soak the beans overnight.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-White-Bean-Soup-4.jpg

Drain the beans.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-White-Bean-Soup-5.jpg

Put the beans in a large pot or 6-quart Dutch oven. Cover with 4 quarts of water and bring slowly to a simmer over medium heat, skimming any scum that rises to the surface. Simmer gently until the beans are tender, about 1 hour. Replenish the liquid with additional water as needed.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-White-Bean-Soup-7.jpg

Season the mixture with salt and pepper. Add the diced carrots and turnips and simmer until tender, about 15 minutes. Add the parsnip and continue to simmer until all of the vegetables and beans are quite soft, 15-30 minutes longer. Taste the soup and adjust seasoning, adding more salt or pepper to taste, if desired.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-White-Bean-Soup-8.jpg

Pass the soup through a food mill to puree, or use an immersion blend to blend the soup till it reaches the desired texture. In Jefferson’s time it would have been passed through a sieve to make a very smooth and light puree, but it is a very time consuming process for a large batch of soup like this. The food mill will create the most authentic texture in a short amount of time. An immersion blender will make the soup thicker, less silky and less refined, with a texture that is not as authentic. It will still be tasty, though.

Add the chopped celery ribs to the puree and simmer gently for 15 minutes more. If the soup is too thick, thin it with more simmering water.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-White-Bean-Soup-9.jpg

Butter the bread slices and toast them in a skillet on medium heat, turning frequently, until golden. To make the dish pareve or vegan, use a dairy-free bread and rub the bread lightly with olive oil instead of butter before browning.

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-White-Bean-Soup-11.jpg

Cut the toasted slices into bite-sized pieces and divide them among 8 warm bowls.

Ladle the soup over the toasted bread cubes. Serve hot. I like to garnish each serving with a few small bread cubes on top. Note: to make this soup vegan/dairy free, omit butter and use a dairy-free bread… not necessarily traditional, but an easy sub to make. 🙂

image: https://toriavey.com/images/2012/02/Monticello-White-Bean-Soup-Main.jpg

Recipe and Research Sources

The Meikelham and Trist Manuscripts as printed in Dining at Monticello (2005), transcribed and edited by Damon Lee Fowler. Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Jefferson, Thomas (collective works compiled 1984). Jefferson Writings: Autobiography, Notes on the State of Virginia, Public and Private Papers, Addresses, Letters. Library of America, Des Moines, IA.

Wulf, Andrea (2011). Founding Gardners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation. Knopf, New York, NY.

See the full post:https://toriavey.com/toris-kitchen/what-thomas-jefferson-ate-white-bean-soup-2/#abPMHtySy94mtI0F.99

Discover more from ReviewFitHealth.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.