In the age of digital streaming, where virtually every song ever recorded is just a few clicks away, vinyl records have staged a remarkable comeback. While streaming offers convenience and accessibility, vinyl enthusiasts argue that the tactile experience and superior sound quality of records offer a unique listening experience.

Does vinyl sound better than streaming?

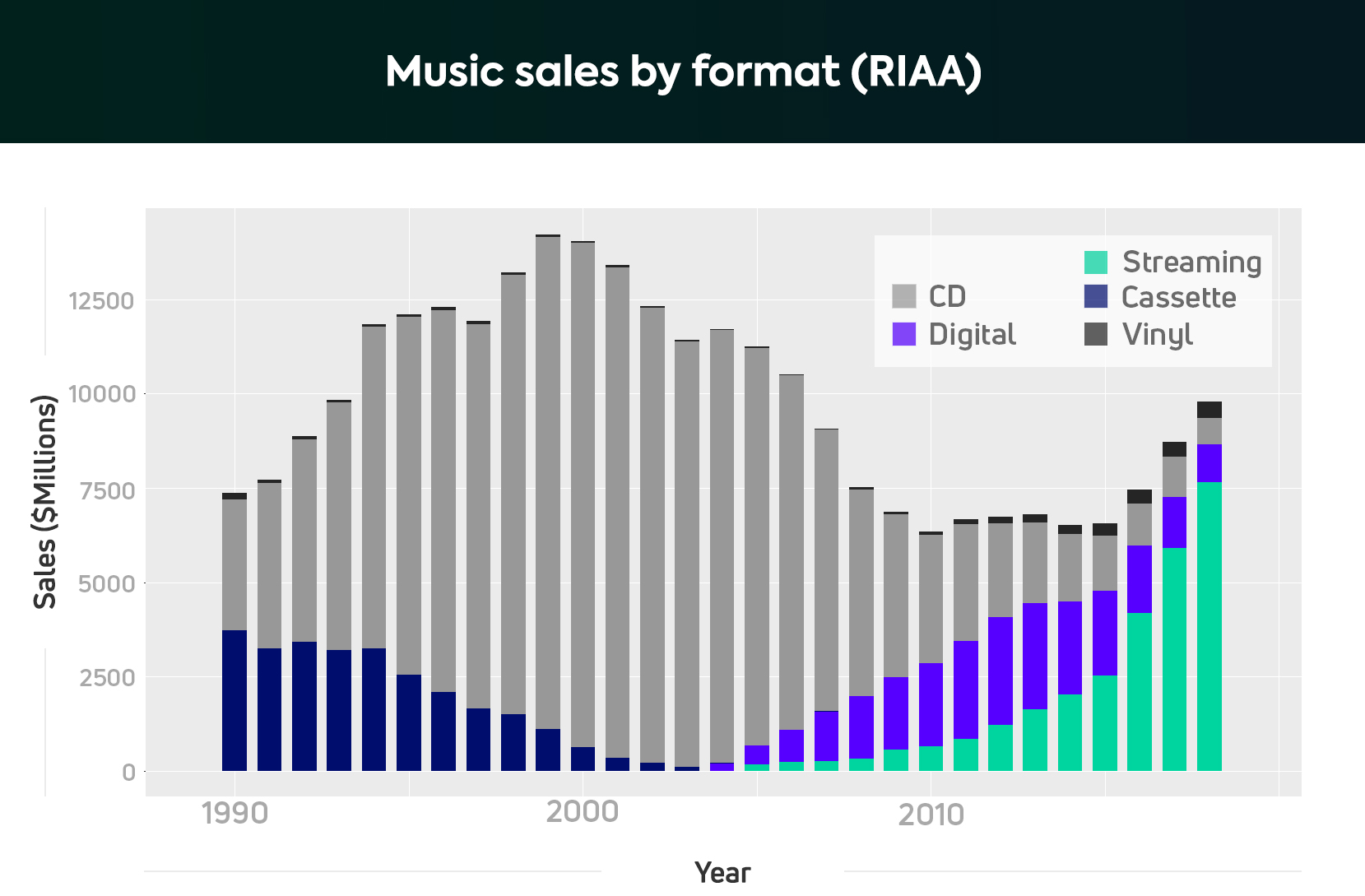

These days the vast majority of the music we experience is stored digitally. The internet has not only changed how we consume music but also how much music we consume, and it has also changed the music itself. Somewhat counterintuitively, vinyl has recently experienced a resurgence in popularity, seeing a year-on-year increase in sales for the last decade. According to the RIAA, vinyl record sales increased by almost 30% in 2020.

Editor’s note: this article was updated on June 22, 2023, to update the style, formatting, and timeliness of the content.

Audio content is more accessible than ever. You can play any song instantly from a pocketable device, so it’s surprising that the concept of collecting physical media hasn’t gone the way of the VHS tape. So what is it about these antiquated, fragile discs that hold such allure?

On the face of it, records are just another consumer product developed to distribute and sell music to the masses. But the record pressing process catapulted audio just as the printing press did the written word. Vinyl does therefore hold something of a cultural and historical significance for music lovers. The iconic status and longevity of the record as a music format cannot be ignored.

Is this resurgence a case of rose-tinted consumer nostalgia, or is there really something magical about the sound of vinyl? Let’s take a look at the underlying technologies.

How do record players and digital music players work?

Regardless of the final delivery medium, a recording has to be made in the first place. Producers capture signals using microphones or directly from instruments, and these recordings are mixed and mastered—more on this process later.

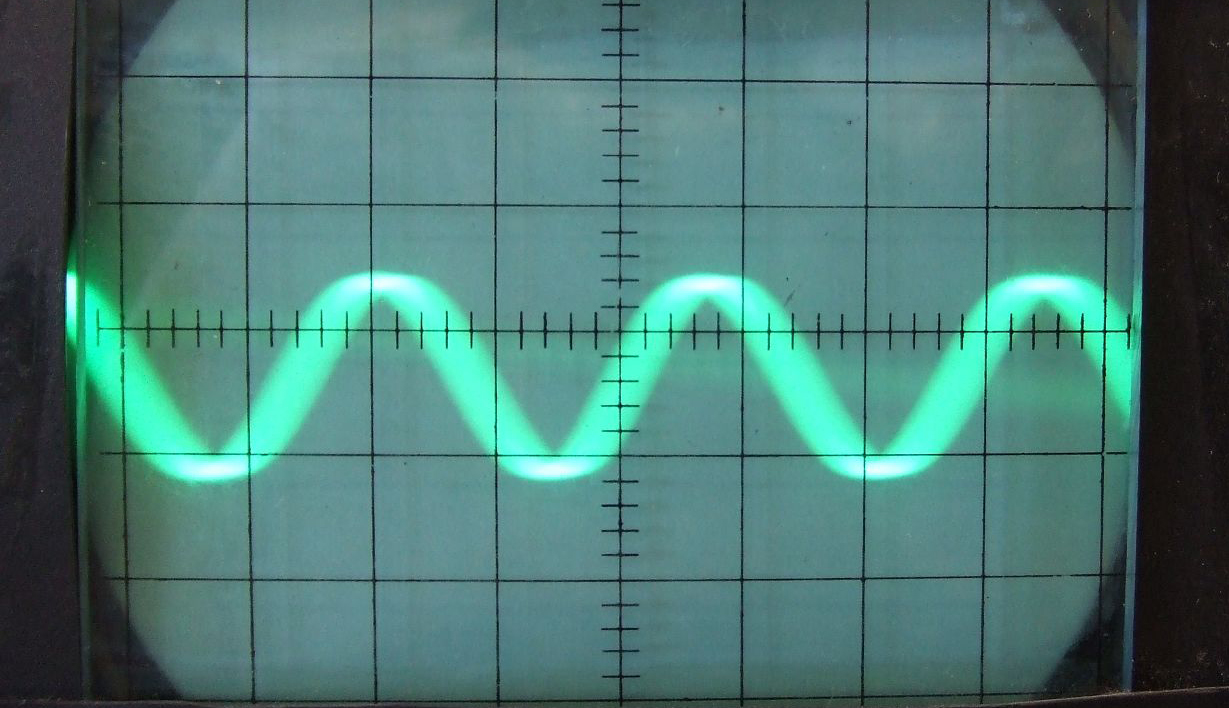

To create a vinyl record, the finished recording is sent electronically to a lathe that cuts into a piece of lacquer. The music’s waveform dictates the shape of the grooves the lathe carves. This lacquer disc is then coated with metal to create the metal master (or “mother”) and is used to create the “stamper” (just a negative version of the mother). The stamper is loaded into a hydraulic press and pressed into vinyl stock, which creates the actual vinyl records.

During playback, your record player’s needle (or stylus) follows the record’s groove and produces an electrical signal using a tiny electromagnetic generator called a cartridge. This can be either a moving magnet (MM) or moving coil (MC)—both use magnets and coils of wire to generate the signal. Once passed through a corrective equalizer and amplified, the electric current generated can create the physical movement of the speakers, which effectively reproduces the recorded sound in an all-analog playback chain.

Vinyl has several physical limitations to consider. If the frequency of the recorded audio is low and the amplitude is too high (loud), the needle becomes prone to bouncing out of the groove and causes the record to skip. Audio engineers apply specific mixing rules to music recorded to vinyl to prevent skips and tracking errors. A standard technique is to pan the bass in the center of the stereo mix.

Top Deals

High-frequency sounds mean the etched groove features very tightly spaced detail, and the needle has to skate around these waves and turn extremely tight corners which cannot consistently be replicated accurately. This can produce objectionable “sibilance,” an unpleasant hissing sound associated with “s” sounds and other high-frequency components.

Compare this to digital audio, where the captured audio signals are sent through an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) so that the computer recording program can process it as a series of ones and zeros. The conversion’s resolution depends on the sample rate and bit depth. For example, CD-quality audio has a sample rate of 44.1kHz, meaning the sound is sampled 44,100 times per second, and 16 bits of data are recorded per sample. Data rates are typically higher than this during the recording, mixing, and mastering process. Playback involves reading this digitally encoded data and feeding it through a digital-to-analog converter (DAC) before passing the amplified signal to headphones or speakers.

Now that we have this basic understanding of how both formats work let’s see if one is sonically better than the other.

What are the sound quality differences between vinyl and digital?

To establish baseline definitions for this discussion, “vinyl” refers to a new, well-made vinyl record played back using the best equipment available. When we say “digital,” we mean a CD or 16-bit/44.1kHz lossless file played using the best equipment available. Higher-quality digital audio options are available, but the 16/44.1 file is the most commonly available commercially. Any increase in sampling frequency or bit-depth will only improve on digital sound quality metrics discussed here.

Frequency response and distortion

Vinyl records can easily cater to the entire frequency range of human hearing and beyond. Quoted limits range from as low as 7Hz to as high as 50kHz, depending on the hardware and any low frequency (rumble) filters applied. However, this doesn’t tell the whole story. Specs vary within the context of the record itself. As the needle moves from the outside towards the record’s center, it becomes harder to pick up high-frequency detail accurately as the spiral gets tighter. Over time, the inner grooves can end up holding less spectral content than the outer grooves due to wear.

The point at which pleasant, “warming” distortion becomes irritating distortion will be different for everyone. Still, some distortion is considered part of the deal with vinyl: it can vary from 0.4% to 3% total harmonic distortion (THD)—DACs typically have values of less than 0.001% THD. If you play records on a poorly set up deck, the inner grooves will suffer from the most pronounced distortion artifacts.

Dynamic range

Digital files allow over 90dB of difference between the loudest and softest sounds, compared to vinyl’s 70dB dynamic range. Digital files, therefore, offer over ten times the dynamic range of vinyl recordings, meaning a much larger difference is possible between the quietest and loudest parts of a recording before noise becomes an issue.

Channel separation

The separation between the left and right channels on vinyl is 30dB, compared to digital files, which exceed 90 dB. This gives vinyl a far more limited soundstage compared to its digital counterpart.

Mechanical noise and surface noise

Turntables generate a low-frequency sound called “rumble,” often caused by the bearings in the drive mechanism. Even with the best turntables, rumble can be generated by warped records or pressing irregularities. It can come through as low-frequency noise, and it’s a serious problem when playing records on audio systems with a good low-frequency response. Even when not audible, rumble can cause intermodulation distortion, interacting with and creating other audible frequencies.

Dust particles that find their way into the record’s grooves can cause playback crackles and pops. With time and repeated replays, the needle can press dust into the vinyl, meaning crackles and pops can get ingrained in the record. Digital files and CDs don’t have these issues since they are read by light beams and use error correction.

Speed variations

The turntable can introduce slight, frequent changes in playback speed known as “wow and flutter.” Wow is a slower rate variation and flutter is at a higher rate. A good turntable will have wow and flutter values of less than 0.05% variation from the mean speed value. Variations can also be present in the original recording due to imperfections in the analog recording devices. Since digital systems use precision oscillators for their time reference and data buffers, they are not subject to wow and flutter.

A good turntable can achieve impressive playback specs, given how long ago the discs became standardized. However, compared to the basic specs of an audio CD, the difference in performance is quite clear: digital is objectively more accurate and consistent.

What’s so good about analog sound?

Vinyl has some serious sound quality downsides based on the technical specs, but less-than-ideal specs don’t mean it’s obsolete: some people like the sound of imperfection. In contrast, digital audio has sometimes been criticized as being “cold” or lacking the “warmth” of analog systems. However, this thinking doesn’t align well with how music is produced today.

There are relatively few instances these days where a recording is made solely using analog equipment. For example, an album may be recorded on 2-inch tape but bounced to a digital audio workstation (DAW) for mixing and mastering. Another might be recorded and mixed entirely in the digital domain but then mastered using analog gear. Which will sound best?

How does mastering affect the music we hear?

Although there are no advantages in measured audio quality, vinyl can offer some benefits when the source material is subjected to proper mastering. Mastering is the process by which the final mix is prepared for the delivery medium. It gives albums consistent levels, appropriate gaps between tracks, and an overall sound profile that will translate well across playback systems.

Over the past few decades, due to the removal of the physical limitations of vinyl media and the spread of digitized music, songs have become increasingly loud. A shift occurred in the mid-1990s when artists and their labels wanted their tracks to stand out based on the premise that louder equals better. This was achieved in practice by excessively using dynamic compression and limiting at the mastering stage.

This means that the overall amplitude of the sound wave becomes compressed, forcing the quieter parts of a song to become relatively louder, with a reduction in the dynamic range used within the context of a song. The average level of the audio signal is raised while limiting the peak value at or close to 0dBFS; the maximum level digital media can represent.

labels wanted their tracks to stand out, based on the simple premise that louder equals better

Because of this trend, most commercial music releases became embroiled in a completely unnecessary “loudness war,” forcing them to increase loudness to remain competitive with contemporary releases. It became noticeable that the increased use of compression and limiting resulted in a loss of detail and nuance in the end product. Prominent audio engineers criticized this state of affairs, and it’s often quoted as an argument in vinyl’s favor. Some people prefer vinyl for this reason: music properly mastered for the medium is relatively immune to the effects of the loudness war, meaning good dynamics are left somewhat intact on releases carefully mastered for vinyl.

Does this whole analog vs. digital debate even matter?

Format alone does not ensure quality: you could listen to the most expertly crafted vinyl record in the world, but it wouldn’t matter if you played it through a portable record player with built-in speakers. Likewise, you could have access to uncompressed studio master FLAC files, but it wouldn’t mean much if you were listening over your laptop speakers or via a Bluetooth connection.

Despite the shortcomings we’ve described, the vinyl record is an incredibly durable and elegantly simple medium. Because vinyl requires physical objects to store the music on locally instead of just streaming it from a server, you’ll need to buy and keep hard copies of every album you want to listen to, and that space—and price tag—adds up fast. It’s even worse when you realize that cartridge needles wear down and that your budget for music listening will have to increase if you contract the vinyl bug.

| Vinyl | CD | |

|---|---|---|

Dynamic range | 70dB | 96dB |

Frequency response | 30-50kHz | 2-22 kHz |

Data Format | Analog | Digital |

Bit rate | N/A | 1,411 kbps |

People like vinyl for the experience; it’s a deep, physical connection to music. Some listeners prefer the experience of dusting off the record, lining it up, dropping the needle, and kicking back, instead of just scrolling and tapping a screen. Listeners are more likely to engage in the listening process, and the medium encourages the consumption of a complete album as a piece of work. Sometimes it’s just nice to collect, even if it’s never listened to.

What matters most is supporting your favorite artists. Whether you listen to CDs, MP3s, FLAC files, vinyl, or cassette tapes, it all comes down to making sure your hard-earned cash contributes to those creating great content. Even though digital files are demonstrably superior, it’s totally fine if you enjoy vinyl’s idiosyncrasies. In reality, analog audio is now prized more for its imperfections than its accuracy.

Discover more from ReviewFitHealth.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.