By Prashant Kidambi from BBC.com

Historian

Cricket, it has famously been said, is an Indian game accidentally invented by the English.

By a curious historical irony, a sport that was the exclusive preserve of colonial elite is now the national passion of the formerly colonised. What is equally extraordinary is that India has become world cricket’s sole superpower.

It is a status much savoured by contemporary Indians, for whom their cricket team is the nation. They regard “team India” as a symbol of national unity, and its players a reflection of the country’s diversity.

Cricket Country

“In this last decade,” former cricketer Rahul Dravid noted in 2011, “the Indian team represents, more than ever before, the country we come from – of people from vastly different cultures, who speak different languages, follow different religions, belong to different classes.”

But the link between cricket and the nation was neither natural nor inevitable.

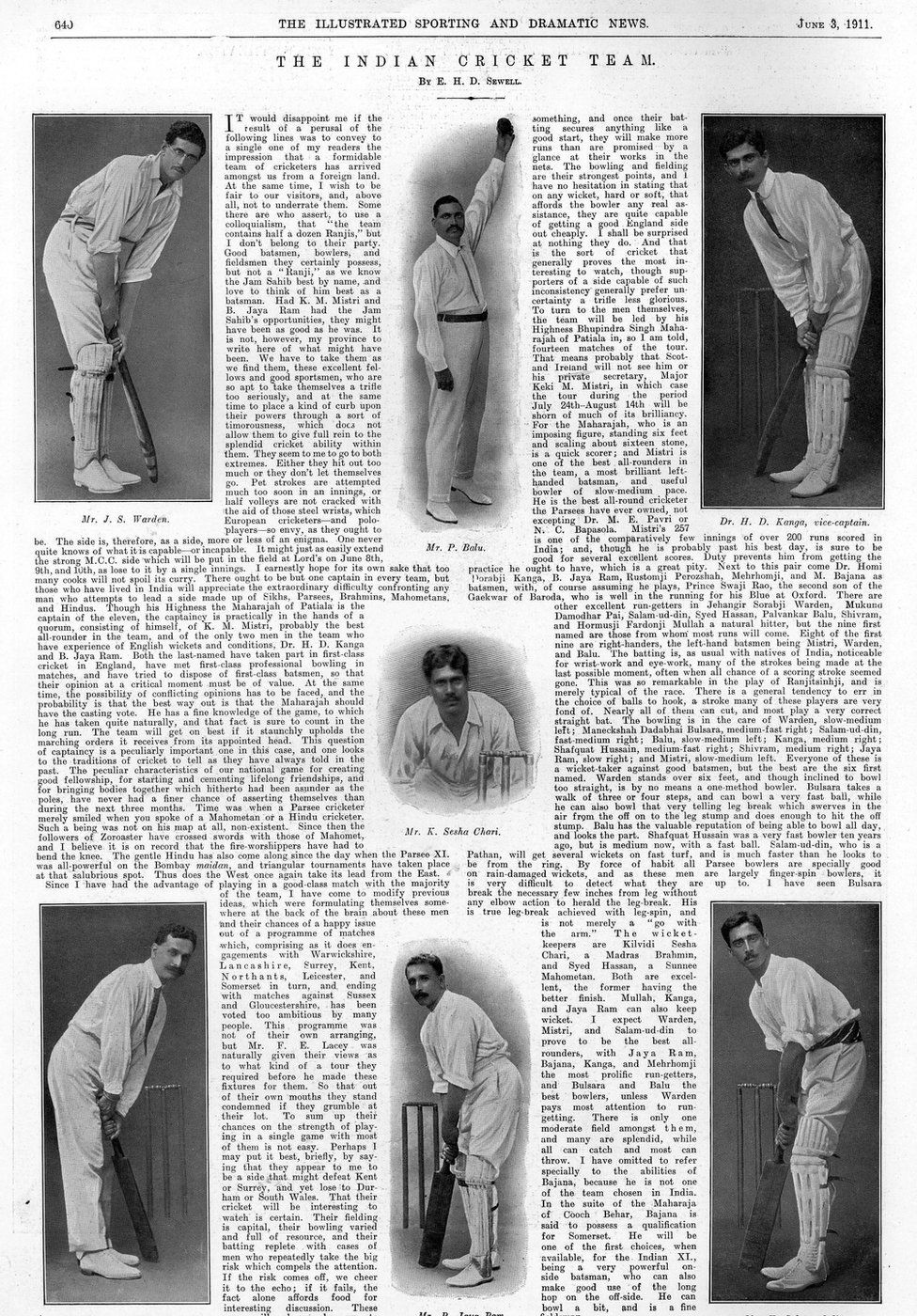

It took 12 years and three aborted attempts before the first composite Indian team took to the cricket field in the summer of 1911. And contrary to popular perception – fostered by the hugely successful Hindi film Lagaan – this “national team” was constituted by – and not against – empire.

A diverse coalition of Indian businessmen, princely aristocrats and publicists, working in tandem with British governors, civil servants, journalists, soldiers, and professional coaches made possible the idea of India on the cricket pitch.

Because of this alliance between colonial and local elites, India was represented by a cricket team in imperial Britain more than a hundred summers before Virat Kohli and his men embarked on their campaign for the 2019 ICC World Cup.

The magical Ranji

The project to construct an “Indian” cricket team had a long and tortuous history. The idea was first floated in 1898, following the stunning rise of Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji or Ranji, an Indian prince who bewitched Britain and the wider imperial world with his sublime batting.

Indian cricket promoters sought to capitalise on Ranji’s celebrity in putting together a team. But Ranji, who used his cricketing prestige to become the ruler of Nawanagar, was wary of a project that might raise questions about his nationality and, in particular, his right to represent England on the cricket field. There were some in the English establishment – notably, Lord Harris, the ex-Governor of what was then Bombay – who had never reconciled themselves to Ranji’s astonishing cricketing success and continued to regard him as a mere “bird of passage”.

Four years later, a different imperative was at work. Now, Europeans in colonial India, who sought to attract teams from home, collaborated with powerful local elites to create an Indian team that would showcase the country’s potential as a cricketing destination.

But the venture failed because of fierce divisions between Hindus, Parsis and Muslims over the question of their representation in the proposed team.

A subsequent attempt in 1906 met with the same fate as previous failed ventures.

The years between 1907 and 1909 saw a wave of “revolutionary” violence by young Indians who targeted British officials and their local collaborators. And there were strident calls in Britain to prevent the free movement of Indians into the country.

Curious Cast

Dismayed by the negative publicity generated by these acts, leading businessmen and public figures, along with prominent Indian princes, sought to revive the project of sending an Indian cricket team to London. This was the historical context within which the first “all-India” cricket team took shape.

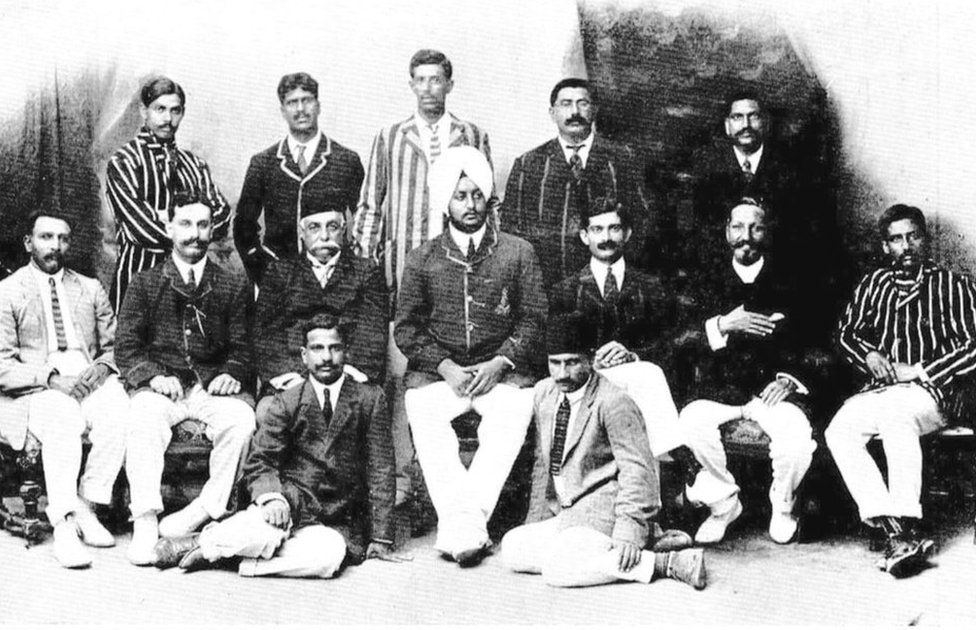

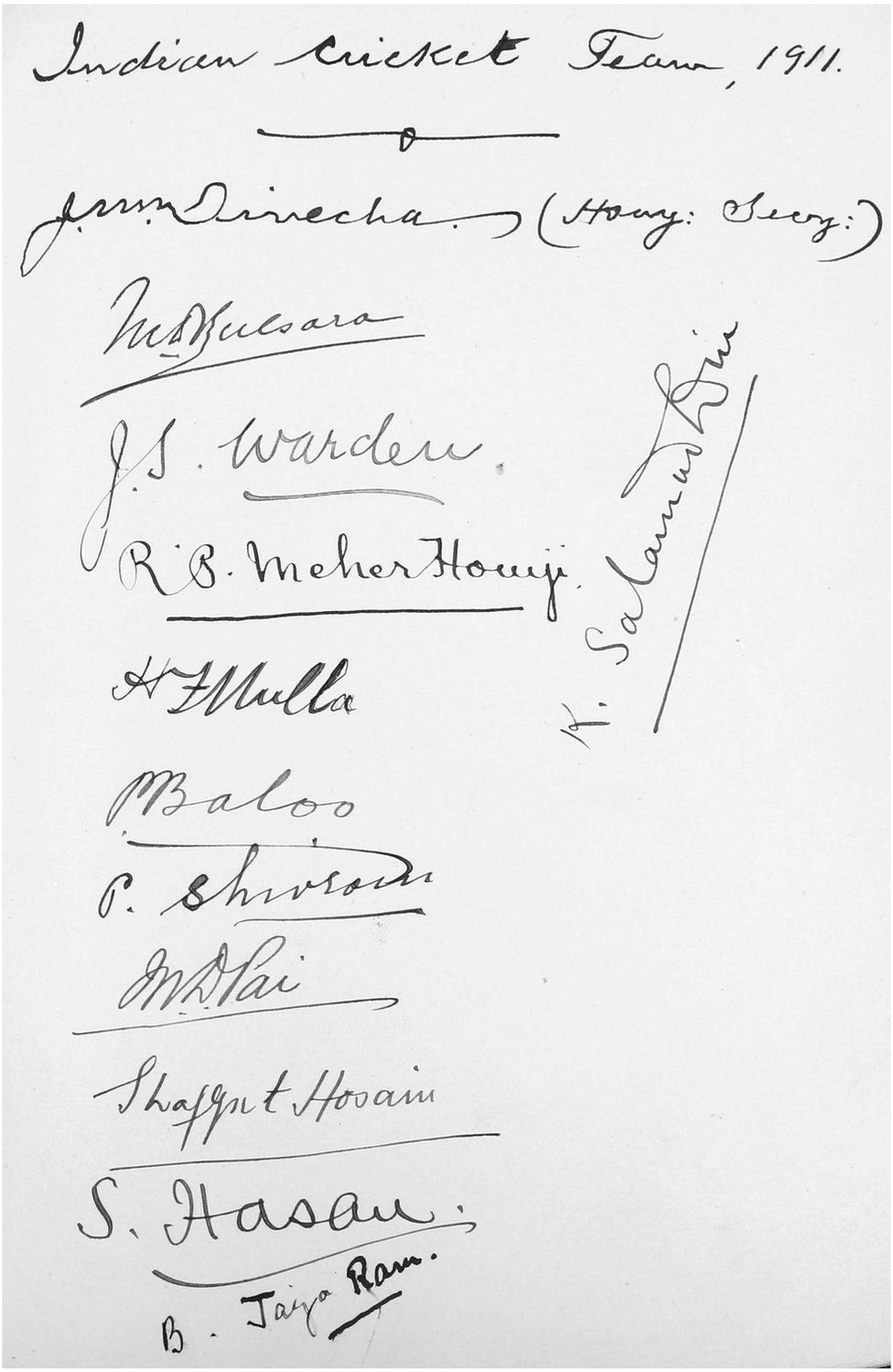

The men who were chosen to represent India on the imperial stage made for an improbable cast of characters.

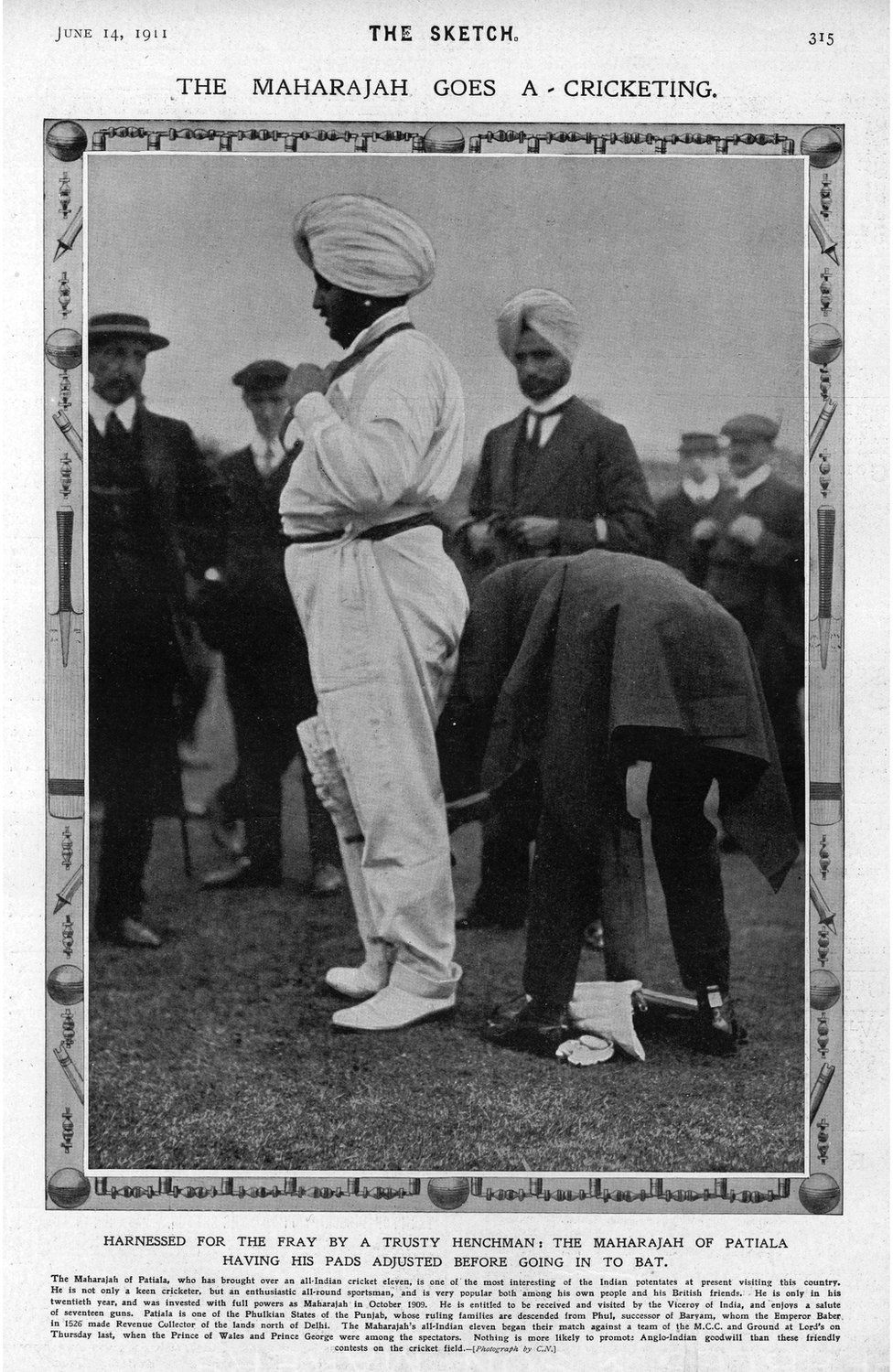

The captain of the team was 19-year old Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, the pleasure-seeking, newly enthroned maharaja of the most powerful Sikh state in India.

The rest of the team was selected on the basis of religion: there were six Parsis, five Hindus and three Muslims in the side.

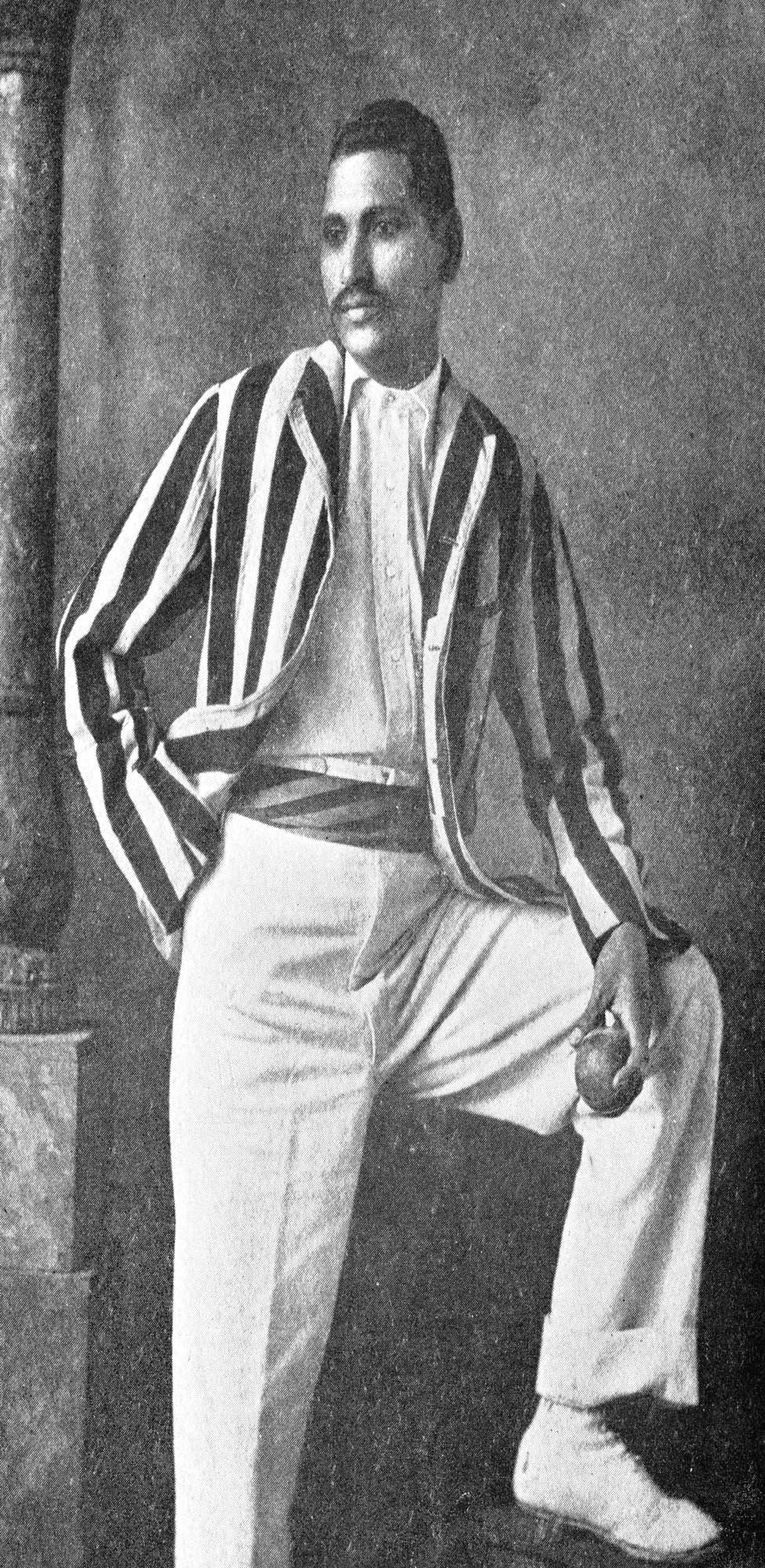

But the most remarkable feature of the first Indian cricket team was the presence of two Dalits from what was then Bombay – the Palwankar brothers, Baloo and Shivram, who overcame the resistance of upper-caste Hindus to become top cricketers of their time.

The composition of this team shows how in the early 20th Century, cricket took on a range of cultural and political meanings within colonial India.

For the Parsis, the cricket field acquired new significance at a time of deepening anxieties about the community’s supposed deterioration. As Hindus and Muslims became more competitive on the pitch and elsewhere, Parsis began to fret about their own decline.

Among northern India’s Muslims too, cricket came to embody a new relationship with the political order established by British rule in the subcontinent.

Notably, the game was an integral feature of the one of the most important educational initiatives in colonial India: to forge a new Muslim political identity. Of the four Muslim players named in the first Indian team, three came from Aligarh, whose most well-known institution – the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College – had been established by the social reformer Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan to promote western learning within his community.

And finally, cricket also became a prism through which Hindu society was forced to reassess the insidious effects of the caste system.

At the heart of these debates was the stirring example of an extraordinary Dalit family, whose cricketing ability and achievements questioned the pernicious system of inequity and exclusion practiced by upper-castes Hindus.

For the Palwankars, cricket made their struggle for dignity and justice against discrimination possible.

Baloo, in particular, became one of the most well-known public figures among his downtrodden compatriots. He was also the hero of the great BR Ambedkar, the architect of India’s Constitution and a Dalit icon.

For Maharaja Bhupinder Singh, on the other hand, the imperial game was an important instrument in furthering his political interests. The embattled ruler sought to use his position as captain of the first all-India cricket team to quell growing imperial doubts about his abilities as a ruler.

Empire loyalism

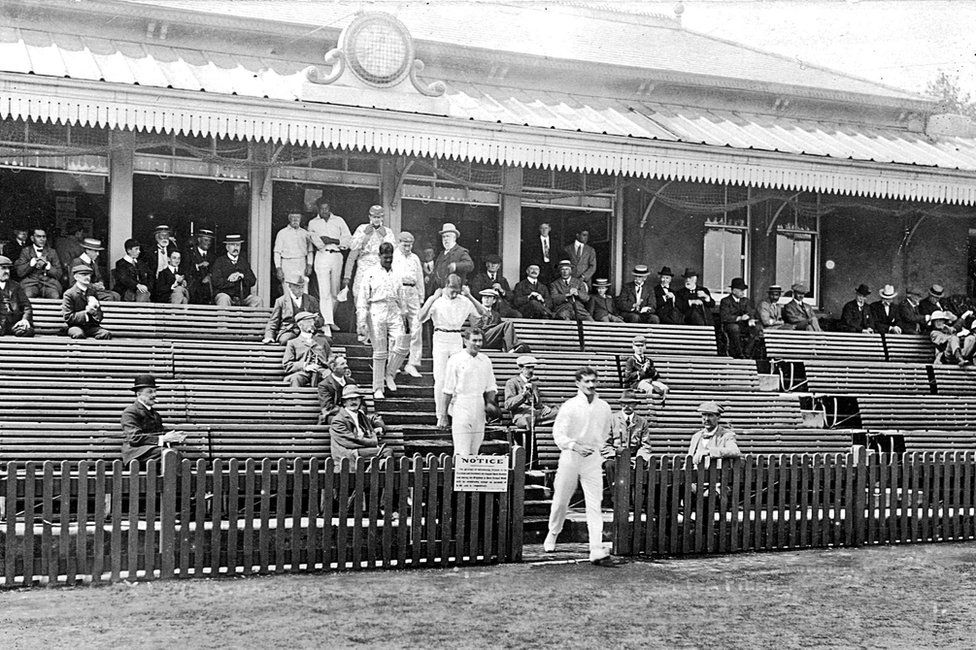

For the empire loyalists who financed and organised the venture, cricket became a means of promoting a positive image of India and assuring authorities in Britain that the country would remain a loyal part of the British Empire.

That was the principal aim of the first all-India cricket tour of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The timing was not a coincidence: it was the year George V was formally crowned king-emperor in London and then travelled to India for the Delhi Durbar.

It is salutary to recall this long-forgotten history at a time when cricket in the subcontinent has become the vehicle of a shrill hyper-nationalism that views sport as “war minus the shooting”.

Dr Prashant Kidambi is associate professor of colonial urban history at the University of Leicester and author of Cricket Country: The Untold History of the First All India Team (Penguin Viking)

Viewpoint: How the British reshaped India’s caste system

19 June 2019

Rivals on the field, friends off it

16 June 2019

Discover more from ReviewFitHealth.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.