Video: Emergency Care Options Dwindle in the East Bay

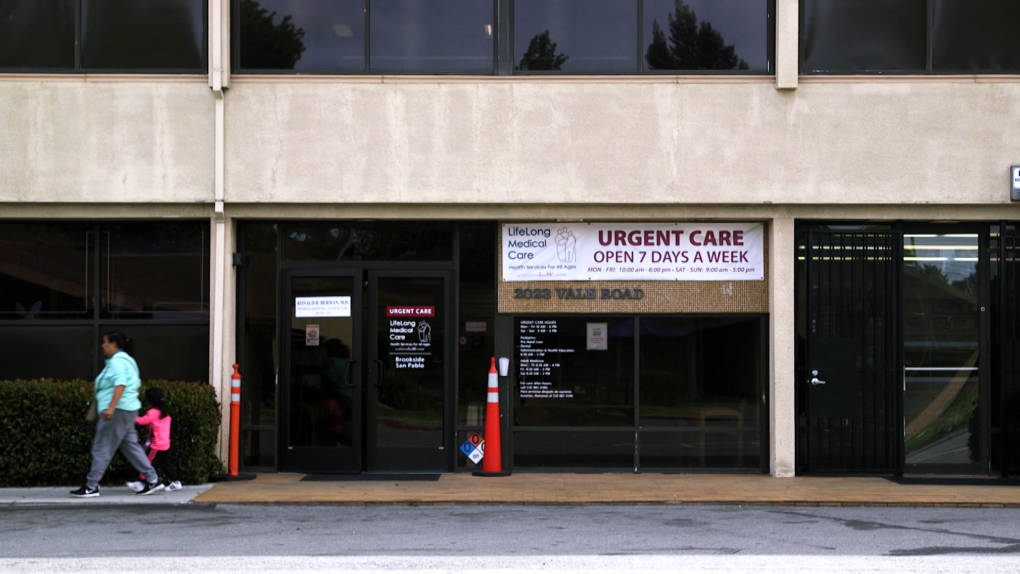

In a cramped office in San Pablo, a group of health care providers work as fast as they can to treat a growing line of people seeking treatment. Already, at the break of dawn on this April morning, the line is spilling down the hall and out the front door.

Since LifeLong Medical Care opened in April 2015, the staff has grown used to long lines. The facility opened the same week that neighboring Doctors Medical Center (DMC), one of West Contra Costa County’s most relied-upon hospitals, closed its doors after years of financial strife.

Located directly across the street from the now-shuttered DMC, LifeLong is one of the few urgent care facilities left to serve more than 400,000 residents in Richmond and surrounding cities.

Unlike DMC, LifeLong provides only urgent care, is not a full-service hospital and does not have an emergency department. When patients come in with life-threatening emergencies, LifeLong’s staff does their best to connect them to services elsewhere. But there aren’t many options nearby.

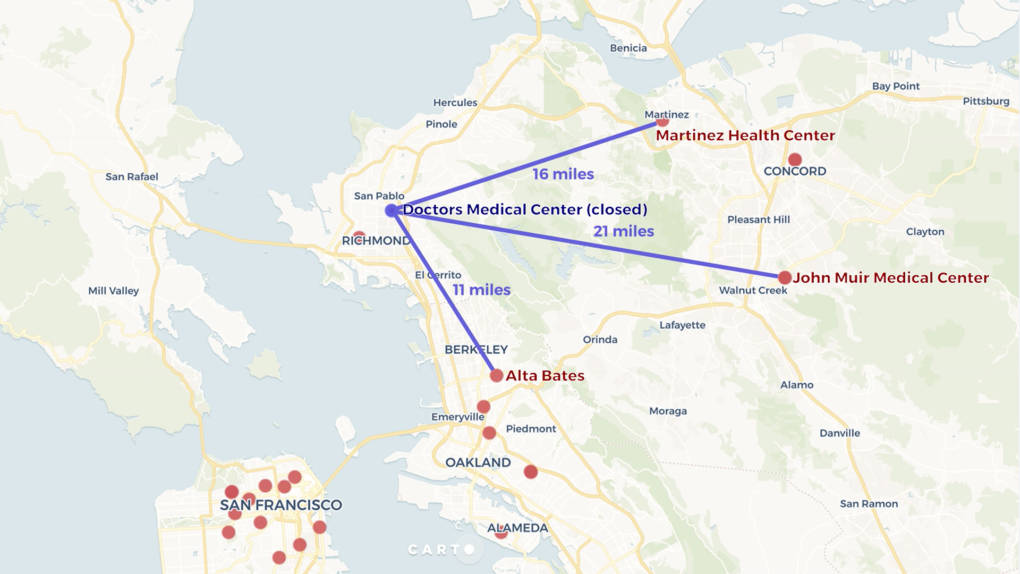

Alta Bates in Berkeley is 11 miles south and the Contra Costa Regional Medical Center in Martinez is 16 miles to the east. The only other high-volume emergency option is John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek, more than 20 miles away. Add in rush-hour traffic, and travel times from West Contra Costa County increase dramatically.

Now that DMC is closed, the only emergency room left in the Richmond/San Pablo area is Kaiser’s Richmond Medical Center, a 50-bed hospital. In a statement, Kaiser reported a 50 percent increase in ER visits since DMC closed in 2015.

“Time is muscle,” said Dr. Desmond Carson, an urgent care physician at LifeLong. The farther that residents have to travel, Carson said, the worse their chances are of surviving.

For East Bay residents, access to emergency care might soon be getting even harder to come by. In 2016, Sutter Health, which owns Alta Bates Medical Center in Berkeley, announced it will close the emergency room and consolidate those services into its Oakland location at an unspecified time in the future. The Oakland facility is located 2.6 miles south of the Berkeley facility.

In a statement, Sutter Health explained that California’s seismic regulations require the Alta Bates campus to cease operating as a hospital by 2030. Aware of the community’s concerns, Sutter also assured that this transition won’t be abrupt either.

According to Dr. Brian Potts, who runs the emergency department at Alta Bates, a planned transition that could take as long as 10 years will allow enough time to build the infrastructure necessary for what he projects to be the biggest emergency room in the East Bay.

And the transition will be worth it, said Potts, explaining that consolidating services under one roof, rather than having two separate emergency rooms miles apart, will improve quality of care.

Many in the community fear the closure of Alta Bates’ emergency department is part of a similar story: hospital leaders more concerned with cost efficiency than providing care, no matter the cost. As a result, East Bay residents are facing life in a hospital desert. Gunshot wounds, delivering babies and heart attacks could become even more life-threatening when the move does happen.

“The harder you make it to get to that care, the more difficult it’s going to be and the more of a need it’s going to be,” said Marty Lynch, LifeLong’s CEO. “There’s no question that folks in Richmond and folks in San Pablo need a good system of emergency care.”

Kathleen Sullivan, a community leader in Richmond who fought to keep DMC open, found herself rushing her husband to the emergency room when he was shot in the streets last year. Doctors at Kaiser’s Richmond facility, she said, couldn’t operate on him and spent about 30 minutes determining which hospital to send him to. They finally came to the decision to send him to John Muir Medical Center, over 20 miles away in Walnut Creek.

By that time, it was 5 p.m. It was bumper-to-bumper traffic, all the way there.

But Sullivan’s husband was lucky. If the bullet had pierced just a quarter of an inch in either direction, it would have hit a major artery, and he would have died long before they left town. Sullivan calls it a death sentence to be shot or hurt in Richmond. She said residents often don’t even bother to call the ambulance. “What’s the point?”

“Look at other cities that have a hospital that’s sitting in their town. They’ve found the resources to go in and renovate the hospital and keep it there,” said Sullivan. “Hospitals lose the incentive to work through alternatives because it’s not financially lucrative to try to meet halfway for communities who are primarily Medi-Cal.”

DMC, whose medical base was about 80 percent Medi-Cal recipients, closed after years of financial crisis brought on, in part, by this reimbursement model.

Dr. Desmond Carson, who worked at DMC for 15 years, said the hospital closed for a reason.

“If there’s a Nordstrom, there’ll be health care. Health care follows the dollar, simple as that,” he said. It’s not profitable, he added, to serve struggling black and brown communities.

Mariana Moore, a director at the nonprofit Richmond Community Foundation, agreed.

“If you look at the reimbursement model from the federal level down to local hospitals that serve primarily Medi-Cal patients, it’s not a sustainable financial model,” said Moore. “These closures happen in communities that are people of color, that are low income, that have less political power, and it’s just the story of our country, as well as the story [Contra Costa County] in this time.”

To LifeLong CEO Lynch and his staff, the memory of the DMC closure lingers every day at the urgent care.

“There’s a long history of feeling that the community did not necessarily get served as it needed to be served,” Lynch said. “There’s a long history of feeling like, ‘Well, why was the county medical center built in Martinez (in 1998), far away from West Contra Costa.’ The community felt that was both a mistake and a conscious disregard for the needs of poor communities.’”

Lynch remembers what DMC meant to this high-need community. Every day, he sees reminders of what the community lost: not just in the number of people crowded into his waiting room, but in the feeling that the community is not being heard.

Additional reporting by Nuria Marquez Martinez.

This story was updated to include the distance between the Alta Bates Berkeley facility and the Oakland facility.